The $135 million church building no one can use

How a Netflix show and AI helped me see how we keep building monuments to church models that are already dying by the time we move in.

I watch Owning Manhattan, without apology.

I can’t help it - I love real estate and design, and I love the nostalgic feeling I get seeing the apartments (and the views!) since I lived in New York City in the late 1990s, and went to seminary there.

The show is also decidedly escapist - and decidedly non-spiritual. Ryan Serhant and his high-powered team selling $50 million penthouses to oligarchs, wearing clothes that cost more than I make in a year. Chasing success in the two-dimensional realm of having more of everything. Doing more than anyone else.

I find it kind of soothing and almost sociological to drop in on a world that is utterly foreign to me.

So the last thing I expected to see was someone having a personal spiritual crisis.

AND a bunch of people having a real estate spiritual crisis!

In the show’s finale, Ryan Serhant - the show is built around him and his eponymous company - breaks down crying.

He’s successful in almost every aspect of the word: He’s rich, powerful, good-looking, smart, talented. He inspires people to be their best. He has a loving wife and a small daughter. He’s ridiculously charismatic.

And he’s in tears because his family means so much to him but he never sees them. He has no time with his child. He never takes time off. His stress levels are killing him.

His friend, who’s in recovery, gently suggests that Ryan is addicted to power and financial success - and he doesn’t disagree.

He’s spiritually struggling while living a wildly successful life.

This made me sit up on the couch.

I’m sure they didn’t mean to, but Netflix created an advertisement for the church.

It shows how nothing - nothing - matters more than understanding that the meaning of life is love.

Is being made in the image of God, and called to live a life that connects with the love of God, and shares that love.

And that we do not have this - we can have everything else, and still have nothing. We’re clanging gongs and noisy cymbals.

Not even this nakedly ambitious show about nakedly ambitious people can cover up that what we do in ministry is worth more than any measure of worldly success.

And that was just the show’s finale. Before that,

I had already started down a huge rabbit hole when the Serhant team spends lots of time struggling to sell a church building.

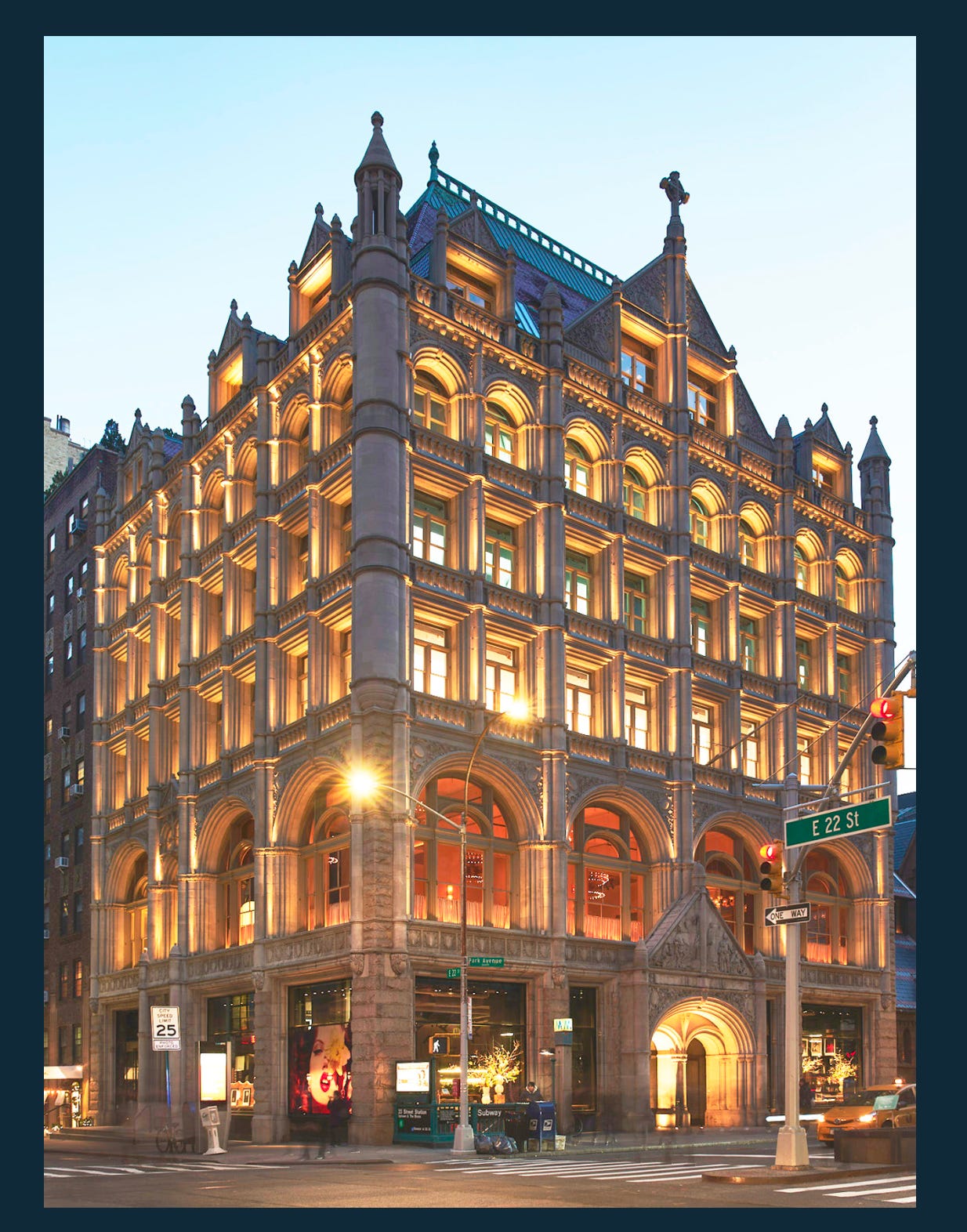

It was 281 Park Avenue South.

As they did a video tour of the building, it was immediately familiar to me. The stone and the arches. The crosses above the doorways. The likeness of Bishop Samuel Seabury - the first American Episcopal Church Bishop. The chapel (now a restaurant…).

I was sure I had seen it before - and I recognized the design, and all the elements. I knew it had been part of the Episcopal Church.

But I was stunned that I did not know its history.

This was the first Episcopal Church headquarters.

I was immediately obsessed with both why I didn’t know this story - and what the story was!

I did an AI-driven deep-dive, and this is what I discovered….

Built in 1894 with Cornelius Vanderbilt and J.P. Morgan money, as ‘a physical symbol of the Church’s permanence and commitment to global evangelism’. It cost $500,000 then - over $18 million in today’s dollars. The asking price now is north of $135 million.

The AI report is long (and you can access it below), but here are the highlights:

The building is a Flemish Renaissance fortress on “Charity Row” (where all the benevolent societies clustered).

It was the first ‘command center’ for the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society (DFMS) - the Episcopal Church’s formal name.

The whole concept of having a ‘church center’ was brand new - and it took 25 years to convince church leadership that it was needed.

It was designed to coordinate missionaries going west (past the ‘Western Reserve’ of Ohio).

Nicknamed just ‘281’ - so iconic that Episcopalians in Hawaii got license plates reading ‘281’ as tribute to the headquarters.

The theology carved in stone:

The frieze over the entrance shows St. Augustine preaching to ‘barbarians’ in England (6th century) next to Bishop Samuel Seabury preaching to ‘barbarians’ in America.

It’s symbolic of the direct line of apostolic succession, literally set in stone. The connection through the Anglican Church into the (fairly new) Episcopal Church in the US.

Every detail of the building was a sermon about church mission and permanence.

It worked perfectly—for about 30 years.

By 1926, the building was already listed for sale. It was too expensive to maintain.

By the 1950s, it was hopelessly overcrowded:

Departments scattered to Greenwich, Connecticut and Evanston, Illinois (30 miles and 1,000 miles away).

The Bishop was commuting because there was no room in the building.

New employees required ‘the services of an architect’ just to find desk space for everyone.

1963: The church traded up

281 was sold, and the Episcopal Church built 815 Second Avenue near the UN.

A modern, efficient, corporate headquarters made of glass and steel—the opposite of 281’s stone fortress, with Christian theology carved in every detail.

In the mid-20th century, this was the future: streamlined, professional, centralized.

This was the height of the popularity of the Episcopal Church - and mainline Protestantism in the US.

Fast forward to today:

815 Second Avenue is running a $2.5 million annual deficit.

The ‘efficient’ building is now the albatross in a dwindling church.

Meanwhile, 281 has been sold and resold:

To Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies (1963-2014) - kept the Charity Row legacy alive.

Landmarked in 1979 (can’t be gutted or erased).

To developer Aby Rosen (2014) for $50 million, plus $30 million renovation.

Anna Delvey tried to lease it for her fake “Anna Delvey Foundation” (failed, she went to prison).

Fotografiska photography museum took it (2019-2024, just closed in September. The official reason: ‘not conducive to expanded gallery space’).

The building has resisted every secular use.

And this is where Ryan Serhant came in. And me, too.

The history - and the plight of 281 Park Avenue South - is unexpectedly emotional for me.

I see so clearly how the drive to build it was evangelical - creating both a space that announced the message of the church in the most powerful city in the country, and a place to gather and train missionaries.

The building - and the movement behind it - were a new way to look systematically at a network of congregations and institutions that before this, were mostly united in name only.

And how almost as soon as it was completed, it was outdated.

Then we moved fully embraced the corporate, centralized business model, and moved into a space that reflected that.

Now this space, too, is a burden to the church - and the original structure is still there.

Still beckoning us - almost daring us - to admit we cannot reduce its spiritual power and symbolism to monuments of consumerism.

And inviting us to come full circle. To see that we are, again, on the verge of expanding the reach of the Gospel into the mission field of a new land.

The irony will not let me go:

I discovered 19th century church history through a 21st century real estate show with an unexpected (and probably unintentional) spiritual longing.

I researched it with AI, and I’m writing about it on Substack.

And through it all I can see that the core of what we do as church has never changed. And it has never stopped being relevant to the time we live in.

We’re just navigating a new landscape. And while we (blessedly) no longer refer to them as ‘barbarians’, we are still surrounded by people who need to hear Good News.

We just reach them in new ways.

The building is still for sale.

(I’m struggling to believe that God does not want me to try and buy it. So far my lack of $135 million is convincing me. But just barely…).

And I really want Ryan Serhant to know how much God loves him.

Want to read the full AI research on 281 Park Avenue South?

I’d also like to share a link to the Baptist Cathedral in Tblisi Georgia where the most amazing work is going on. Bishop Malkhaz Songulashvili thinks through Jesus’s mind and heart and soul in ways that create the most profound contributions to the needs of the people.

Our church is a supporter and partner church with them. May he inspire others.

https://peacecathedraltbilisi.org/

Or perhaps L’Arche Community.